Table of Contents

- What West End Girl Is About

- Pussy Palace and the Duane Reade Lyric

- The Role of the “For Data Storage Only” Disclaimer

- How the Merch Rollout Actually Gained Momentum

- Why USB Releases Are Showing Up Again Now

- Gimmick or Narrative Extension?

- Other Album and Media Releases That Cut Through the Noise

- So Who Would Want This — and Who Wouldn’t

- Want More Reads

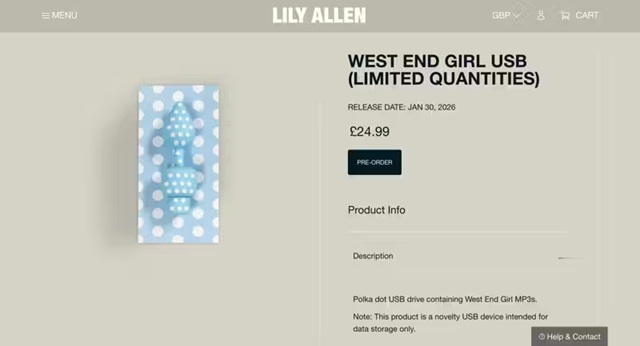

Lily Allen is selling a USB drive as merch for West End Girl. The USB contains the album, it’s official merch, and it’s shaped like a butt plug.

That shape is sexual. Plain and obvious. You don’t need context or analysis to clock it. You see it once and your brain already knows how to read it. That’s why it didn’t drift quietly through the internet. Sexual objects never do, especially when they show up outside the places people expect them. A butt plug–shaped object on a phone screen doesn’t get a neutral reaction. It gets a reaction.

People stopped scrolling.

Some people laughed. Other people felt awkward. Some people thought it was funny. Others thought it was unnecessary. Almost nobody ignored it.

What matters is that the conversation didn’t end once people understood what it was. Knowing it was “just a USB” didn’t shut anything down. It shifted the focus.

The question stopped being what is this thing? and became why make this thing at all?

- Why turn a specific lyric into a physical object?

- Why make it collectible instead of forgettable?

- Why make it something people would argue about instead of scroll past?

That’s why this merch traveled fast and stuck around longer than most drops. The reaction wasn’t about shock alone. It was about intent — and whether the object was saying something, or just daring people to react.

What West End Girl Is About

West End Girl is an album about a relationship falling apart after the damage is already done. It isn’t about the big blow-up or the dramatic confrontation. It’s about what comes next — the quiet realization, the awkward details, and the stuff you can’t unsee once you’ve noticed it.

A lot of the songs focus on betrayal, but not in a sweeping, romanticized way. There’s no grand speech about heartbreak. Instead, the album keeps returning to the aftermath: walking into rooms that feel different, noticing habits that don’t add up, and realizing too late that someone has been living a parallel life right next to you.

That’s where the idea of an “emotional inventory” comes in. The record keeps track of things:

- bags left out

- apartments that don’t feel neutral anymore

- objects that suddenly mean more than they should

- small, practical details that turn into proof

These aren’t metaphors doing heavy lifting. They’re concrete. You could point to them. You could pick them up.

Settings matter just as much as objects. The album is rooted in very specific places — city apartments, pharmacies, everyday errands. Nothing is stylized or dreamy. The mundanity is the point. Betrayal doesn’t show up with a soundtrack. It shows up in ordinary spaces, during ordinary moments, when you weren’t braced for it.

That’s why context matters so much when talking about the merch. Without knowing what the album is doing, the USB just reads as a random provocation. With context, it’s clearly tied to how the record tells its story.

The album isn’t obsessed with sex for shock value. Sex shows up as evidence. It’s one of the ways the narrator realizes what’s been happening without being told outright. The objects aren’t exciting or playful. They’re unsettling because of what they confirm.

Understanding that changes how the merch reads. It stops being “a sex thing for attention” and starts reading as a physical callback to how the album works — by turning everyday discoveries into moments you can’t shake.

Pussy Palace and the Duane Reade Lyric

The line that kept getting pulled out of Pussy Palace is this:

“Duane Reade bag with the handles tied /

Sex toys, butt plugs, lube inside /

Hundreds of Trojans…”

Most coverage zeroed in on it for the same reason: it reads like a snapshot, not a metaphor. Articles from People, The Cut, Grazia, and others all treated the lyric less as “songwriting” and more as a moment of discovery frozen in time.

Across write-ups and fan threads, the Duane Reade detail is usually described as grounding rather than symbolic. It places the scene in a real, recognizable setting and lets the listener do the math on their own. The bag becomes proof, not drama. That’s why the image traveled so far online. It wasn’t treated as a clever turn of phrase — it was treated like evidence you weren’t meant to see, but can’t ignore once you have.

And that’s where the song reframes infidelity. Not as something cinematic or secretive, but as something exposed through ordinary leftovers. No confrontation required. Just a moment where everything clicks, and there’s no way to unsee it.

This is the emotional center the rest of the conversation keeps orbiting — not the merch, not the headlines, but that one plain, uncomfortable image people couldn’t shake.

“Sex toys are still seen as a taboo subject because they are, you know, related to masturbation and female pleasure. … The only way to make taboo subjects no longer taboo is to speak about them openly and frequently and without shame or guilt.” ~ Lily Allen, on her sex toy with Womanizer

The Role of the “For Data Storage Only” Disclaimer

The “for data storage only” line didn’t just exist for legal reasons. It became part of how people talked about the merch.

Legally, it’s obvious why it’s there. Labeling it as a novelty USB keeps it out of sex-toy rules, safety standards, and all the stuff that comes with that category. That’s standard practice, not a statement.

Culturally, though, the wording landed hard because it was so flat. No jokes. No playful tone. Just a blunt line saying exactly what the object is and isn’t. That contrast — between a straight-out butt plug and very dry language — is why people kept screenshotting it and sharing it.

Instead of shutting the conversation down, the disclaimer pushed it forward. It gave people something concrete to react to. Once the “is it usable?” question was settled, the discussion moved on to why this exists at all. The disclaimer didn’t end interest; it redirected it.

How the Merch Rollout Actually Gained Momentum

The USB didn’t suddenly appear online with no context.

People had already seen versions of it around the album launch period. Photos from events circulated quietly at first, which sparked speculation before anything was officially explained. That early ambiguity mattered.

On social media, the rollout stayed light on explanation. A post here, an emoji there, but no long captions spelling out intent. That left room for interpretation, which is exactly what kept people talking.

By the time press coverage picked it up, the conversation was already happening. Articles weren’t breaking the story — they were catching up to something fans were already sharing, joking about, and arguing over. Coverage followed attention, not the other way around.

Why USB Releases Are Showing Up Again Now

USB releases aren’t new. Years ago, artists used them all the time — sometimes packaged as merch, sometimes handed out at shows, sometimes even left around cities for people to find. They were a way to feel digital and physical at the same time.

They faded out when streaming took over, mostly because convenience won. But now they’re coming back for a different reason.

Streaming platforms are crowded, algorithm-driven, and hard to escape. Physical formats offer artists a way to step outside that system again. USBs, in particular, let artists release something tangible without leaning on nostalgia.

They function differently from vinyl or CDs in a few key ways…

- Bypass streaming platforms entirely

- Act more like collectibles than replacements

- Allow bolder, stranger designs

- Keep the release out of algorithm cycles

A USB doesn’t compete with playlists. It sits next to them, doing something else.

Gimmick or Narrative Extension?

So where does this land?

A gimmick usually exists just to grab attention. Once you’ve seen it, there’s nothing left to say. A narratively consistent choice connects back to the work itself and still makes sense after the initial reaction wears off.

This case sits awkwardly between those two.

It does grab attention. That part is undeniable. But it doesn’t feel disconnected from the album’s imagery or themes. It pulls one detail forward and keeps it in circulation instead of letting it fade with the release cycle.

That tension is why people can’t quite agree on how to categorize it. It’s not random enough to dismiss outright, and it’s not subtle enough to ignore. It exists in that uncomfortable middle space where merch becomes part of the conversation instead of just advertising.

And that’s why it didn’t disappear after the first headline.

Other Album and Media Releases That Cut Through the Noise

Getting attention now is harder than ever. People are scrolling nonstop, algorithms decide what gets seen, and most releases disappear within hours. A few artists and creators did manage to break through — not by shouting louder, but by doing something people couldn’t ignore.

Music Releases That Worked

- Beyoncé – Lemonade

Dropped as a full visual album on HBO before streaming. It forced people to sit and watch, not just listen, and turned the release itself into an event. - Radiohead – In Rainbows

The pay-what-you-want release wasn’t just generous — it became the story. People debated it, shared it, and felt personally involved. - Nine Inch Nails – Year Zero

Used an alternate reality game with hidden websites, phone numbers, and clues. Fans uncovered the album slowly, together. - Frank Ocean – Endless / Blonde

Released a visual project first, then quietly dropped the main album. Confusing on purpose, but unforgettable. - Childish Gambino – 3.15.20

No track names at first. Minimal explanation. Forced listeners to engage on the artist’s terms.

“To celebrate the 30th anniversary of Dookie, Green Day put each track into a different vintage or quirky electronic format — from an animatronic Teddy Ruxpin bear to a Game Boy cartridge, a singing toothbrush, a floppy disk, and even a phonograph cylinder.” ~ People (on Green Day’s Dookie Demastered release)

Physical or Format-Based Ideas

- Prince – albums bundled with newspapers

People woke up to find a free album in their paper. Impossible to miss. - Jack White – vinyl-only releases and hidden tracks

Locked songs behind physical interaction. Turned listening into participation. - Björk – app-based album (Biophilia)

Each song functioned as its own interactive experience, not just audio.

Why These Worked

What all of these have in common isn’t shock or money. It’s commitment.They:

- changed how the work was released

- gave people something to figure out or participate in

- made the release itself part of the experience

- didn’t rely on a single tweet or headline

In an attention economy where most content is disposable, these releases stood out because they refused to be passive. They asked people to stop, notice, and engage — even if only for a moment.

That’s why they’re still remembered.

So Who Would Want This — and Who Wouldn’t

This kind of merch is very much a “know yourself” situation.

- It makes sense if you like collectibles tied to a specific moment, enjoy odd or conversation-starting merch, or want something that instantly reminds you of this album cycle. For those people, usefulness doesn’t matter much — the point is that it’s memorable.

- It’s likely a miss if you buy merch to actually use it, or if you’re prone to impulse buys that end up forgotten in a junk drawer once the novelty wears off.

- And it’s an easy pass if you don’t care about physical merch at all, stream everything, or don’t want to own something that might need explaining later.

Basically, some people will see it as a fun keepsake. Others will see future clutter. Both reactions are fair.

Want More Reads

- Harry Styles Steps into Sexual Wellness with Pleasing’s Double-Sided Vibrator

- Toni Braxton’s Magic Wand – Reveals She Uses A Sex Toy On Her Face

- Hello Kitty Vibrator: History, Safety & Kawaii Alternatives